July 2022

Posted: 7/14/2022 8:49:09 AM

A decades-long rise in traffic deaths in the United States is an outlier among developed nations, even two years into a global pandemic, something author Jessie Singer attributes to layers of dangerous conditions that have been adding up for years.

Singer, who wrote, There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster – Who Profits and Who Pays the Price, gave a presentation on “Rejecting the ‘Human Error’ Explanation” at the July 11 NJTPA Board meeting.

As vehicle safety standards and infrastructure spending have declined in the United States, there has been an increase in the average vehicle size and weight, and the average age of vehicles on the road, leading to a rise in traffic deaths, according to Singer. She doesn’t believe that increases in distracted driving or social deviance during the pandemic should bear the blame for the increase in fatalities.

There is a tendency to put up signs or billboards to address individual behavior but Singer said this leaves in place the dangerous condition. She said enforcement campaigns can also be less effective than physical improvements, because if someone is caught by a police officer one out of five days, they credit good luck for the other four days that they were not caught – and likely won’t change their behavior.

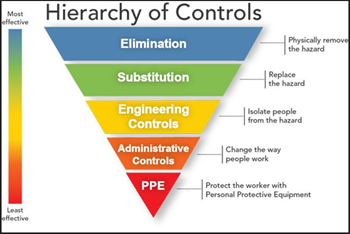

These types of traffic safety efforts exist at the bottom of the pyramid of the Hierarchy of Controls, which looks at ways to control exposure to hazards. Instead, she says the focus should be on the top of the pyramid, which emphasizes eliminating the hazard. For example, narrowing a wide road can force drivers to slow down and drive more carefully because it feels less safe to them.

These types of traffic safety efforts exist at the bottom of the pyramid of the Hierarchy of Controls, which looks at ways to control exposure to hazards. Instead, she says the focus should be on the top of the pyramid, which emphasizes eliminating the hazard. For example, narrowing a wide road can force drivers to slow down and drive more carefully because it feels less safe to them.

Focusing on improving conditions is more effective than focusing on changing the behavior of a few “bad apples,” because it reduces the harm for everyone, Singer said. Education campaigns aim to fix the bad apples, while traffic enforcement tries to get rid of the bad apples, she said.

“The bad apple approach is psychologically satisfying,” Singer said, because that leaves the impression that the system is working fine — it’s just a few people who are bad.

Instead, Singer argues against “trying to perfect people’s behavior on the road” and accept that people will be selfish and want to bend the rules. “Design a system that is safe for them the way they are,” she said, making the comparison that automatic fire sprinklers don’t tell people not to smoke or play with matches – they just prevent harmful accidents.

While education and enforcement campaigns can reach a lot of people, Singer made the case that redirecting that funding to improve just one intersection is more beneficial, even if it affects fewer people, because it will save more lives.

Singer pointed to the City of Hoboken, which has not had a traffic fatality in four years – something virtually unseen in the United States – as an example of how inexpensive changes to street design can have a big impact. One simple evidence-based approach to improve safety is "daylighting" intersections by adding paint or bicycle parking to prohibit cars from parking too close to corners. This improves visibility, making it easier for drivers to see people trying to cross.

She also noted that Sweden has one of the best traffic safety records in the world following the country’s commitment in the 1980s to prioritize reducing road injuries and deaths over how quickly the transportation system moved people. “Some American economists might scoff at that but it’s the only direction you should move in if you want to save lives,” she said.

NJTPA Chair John W. Bartlett, a Passaic County Commissioner, said Singer’s presentation gave the board a lot to think about. He noted that the NJTPA places an emphasis on safety in Plan 2050 and its Street Smart NJ pedestrian campaign, but also as it prioritizes funding for projects, including the NJTPA’s Local Safety and High Risk Rural Roads programs.

“It’s a great way for us to think about standards in what we do,” he said of her presentation.